Tradeswoman’s Entrance (or Peaceful Birth of Gigantic Business)From the bibliographic book «Body and Soul» by Anita Roddick…Gordon is a very unusual man. Although he would be the very last one to admit it, he is at heart an adventurer and a dreamer. I knew that well, so it was not too much of a shock when, after we had sold Paddington’s, he announces that he wanted to take off for two years to fulfil a childhood ambition. The shock came when I learned that ambition was – he wanted to ride a horse from Buenos Aires to New York. I don’t know many men who would contemplate undertaking such an expedition – a daunting 5, 300 mile horseback trek, much of it through remote and dangerous territory – completely alone. It had been his dream to attempt the trip ever since reading Tschiffley’s Ride, an account of a similar trip by the Swiss explorer and writer Aimé Tschiffley in the thirties. «If I don’t do it now, while I am still young and fit,» he explained, «I never will.» I can’t pretend I was thrilled at the prospect of him going off for two years and leaving the children and me, but at the same time I could not help but admire him. It was such a romantic and brave thing to do that it was impossible to be resentful about it. I have always admired people who want to be remarkable, who follow their beliefs and passions, who make grand gestures. I had dreamed that we would giggle our way round the world together at some time, but I simply did not have the courage to contemplate doing what he was about to do, even if I didn’t have the kids to worry about. Some of our friends found the whole thing a bit bizarre; they probably thought our marriage was on the rocks. Actually I thought the fact that Gordon could confidently contemplate such a trip was an indication of the strength of our marriage, rather than the reverse. We had never been possessive of each other and there was a strong streak of independence in both of us. We talked a lot about what I was going to do and how we were going to organize things while he was away. Once we had got rid of the restaurant we realized just how much it had drained us, physically and emotionally, and we did not want to go back to anything like that. Most importantly, I wanted to have a home life, which we had never had before, and I wanted to be able to spend some time with the children, who were then six and four. They had virtually been brought up by their grandmother, and I was concerned that they were growing closer to my mother than they were to me. But I also needed some income, because Gordon would obviously not be contributing anything while he was away and the hotel did not make enough to keep us. WE had not sold the hotel along with the restaurant, for we thought of it as our home. What I would like, I said to Gordon, was a small business that was controllable and only occupied my time from nine to five. The answer, clearly was a shop. So it was agreed. While Gordon researched and planned his expedition – he was already spending a lot of time at the Royal Geographical Society and had tracked down Tschiffley’s wife in London – I would look around for a little shop. «Just a Little Shop»I already had an idea of what kind of shop I would like. It seemed ridiculous to me that you go into a sweet shop and ask for an ounce of jelly babies, and you could go into grocers’ and ask for two ounces of cheese, but when you wanted to buy a body lotion you had to go into Boots and lay out five quid for a bloody great bottle of the stuff. Then, if you didn’t like it, you were stuck with it. One of the great challenges for entrepreneurs is to identify a simple need. People tend not to trust their gut instincts enough, especially about those thing that irritate them, but the fact is that if something irritates you it is a pretty good indication that there are other people who feel the same. Irritation is a great source of energy and creativity. It leads to dissatisfaction and prompts people like me to ask questions. Why couldn’t I buy cosmetics by weight or bulk, like I could if I wanted groceries or vegetables? Why couldn’t I buy small size of cream or lotion, so I could try it out before buying a bottle? These were simple questions, but at the time there were no sensible answers, although it did not take a brilliant business brain to work out that bigger profits accrued from selling bigger bottles. It was also obvious to anyone who thought about it that a lot of the cost of cosmetics was down to fancy packaging. That was another source of deep irritation to me. When I bought perfume all I cared about was what it smelled like. I didn’t give a damn about what the bottle looked like, and furthermore I did not know any women who did! We all suspected we were being conned, but there was precious little we could do about it. I sat down and discussed it with Gordon, telling him the kind of shop I was thinking of opening was one that sold cosmetics products in different sizes and in cheap containers. It made perfect sense to him. (I always think it is odd when I look back on it. The idea for the shop was so simple that it hardly merits being described as an ‘idea’ at all.) For our experience in the hotel and the restaurant we also knew that we could be fast on our feet, and if my idea did not work we would be able to change it or keep tweaking it until it did work. If we couldn’t sell creams and shampoos, we would chuck them out and sell something else. «Doing It Naturally»The other half of the equation was that I wanted to try to find products made from natural ingredients. At the same time, no one was talking much about the advantages or potential of natural products – the green movement had yet to get started – but I knew that for centuries women in ‘under-developed’ areas of the world had been using organic potions to car for their skin with extraordinary success. I knew this to be true because I had seen it with my own eyes, initially in the Polynesian islands. When I arrived in Tahiti the first thing that struck me was the women. I was mesmerized by them. They were straight out of a Gauguin painting, with a wonderful liquid quality. They had absolutely terrible teeth because the chewed sugar cane all the time, but their skin was like silk. It did not make any sense to me. I imagined that, with all the exposure to the sun and the rigours of their lives, their skin would soon become dry and creepy, but even the elderly women had soft, smooth and elastic skin. One of the wonderful things about women, which I don’t think many social anthropologists have fully understood, is that we are bonded by shared experience – by babies and the rituals and problems of our bodies. Men need gambits to open conversations with other men. Women don’t, because a sense of camaraderie and mutual interest already exists between us. All women are interested in looking after their skin, for example, and that is why one women can go up to another, without any hesitation, and ask, ‘How come your skin’s so soft?’ When I asked that question to women in Tahiti they showed me what looked like a lump of cold lard. It was, in fact, cocoa butter, extracted from cocoa pods, which they rubbed on their skins just as they had been taught by their mothers, and just as their mothers had been taught by their grandmothers. It was not only a wonderful conditioner, but it also stopped them getting stretch marks when they were pregnant and soothed skin disorders like eczema. You would often see a group of women sitting around and rubbing cocoa butter on to each other’s bodies. Naturally I tried it myself – I found it was marvelous, although it smelled bizarre. Latter on my travels I kept coming across further examples of women using local natural ingredients for skin and hair care. I loved to watch the native women’s beauty and bathing rituals: I was fascinated by their ingenuity, and made it my business to talk to women wherever I went to find out what they used on their bodies. I saw women eating pineapple, they rubbing the inside of the skin on their faces. Whenever I could I adopted local practices – caring for my body and hair in the same way as the native women, and using the same ingredients. All the conventions I had learned about looking after my body were slowly broken down. It was a revelation to realize that there were women all over the world caring for their bodies perfectly well without ever buying a single cosmetic. These women were doing exactly what we were doing in the west in the way of polishing, protecting and cleansing their skin and hair, but they were doing it with traditional natural substances instead of formulated ingredients. What amazed me was that these raw ingredients which hadn’t been processed in any way, were doing a damn good job. So when I started to look for products for my shop I already knew of about twelve natural ingredients that I had seen working in various areas of the world and which I thought I might be able to use. I make no claim to prescience, to any intuition about the rise of the green movement. At the forefront of my mind at the time there was really only one thought – survival. My husband was going off for two years riding a horse across the Americas, and I knew I had to survive and look after my kids while he was away. By then I also had a name for my embryonic business – The Body Shop. It was not original: I had seen it in the United States where dents were banged out of cars in garage ‘body shops’ everywhere. I must have stored it away in my subconscious memory, and I certainly thought my use of the name was a lot more appropriate. I found out later there were already other stores in the USA which had made the same connection. «Hell-raising, Hair-raising, Money-raising»Before I could make any further progress I needed to raise some money. Gordon and I had calculated I would need about £4,000 to get the business started, but I thought that as we could use the hotel for collateral there would be no problem. Unfortunately, I went about it in entirely the wrong way. I made an appointment to see the bank manager and turned up wearing a Bob Dylan T-shirt with Samantha on my hip and Justine clinging on to my jeans. It just did not occur to me that I should be anything other than my normal self. I was enthusiastic and I gabbled on about my great idea, flinging out all this information about how I had I discover these natural ingredients when I was travelling, and I’d got this great name, The Body Shop, and all I needed was £4,000 to get it started. I got quite carried away in my excitement, but I was on my own. I discovered that you don’t go to a bank manager with enthusiasm – that is the last thing he cares about. When I had finished, he leaned back in his chair and said that he wasn’t going to lend me any money because we were too much in debt already. I was stunned. I went home to Gordon absolutely crushed. ‘That’s it,’ I said. ‘It’s hopeless. The bank won’t give me any money.’ I was ready to give up, bit Gordon is much more tenacious than I am. ‘We will get the money,’ he said, ‘But we are going to have to play them at their own game.’ He told me to go out and buy a business suit, and got an accountant friend to draw up an impressive-looking ‘business-plan’, with projected profit and loss figures and a lot of gobbledegook, all bound in a plastic folder. A week later we went back to the same bank for an interview with the same manger. This time I left the children behind and Gordon came with me. We were both dressed in suits. Gordon handed over our little presentation, the bank manager flipped through it for a couple of minutes and then authorized a loan of £4,000, just like that, using the hotel as collateral. I was relieved – but I was angry, too, that I had been turned down the first time. After all, I was the same person with the same idea. It was clear to me that bank manager only talked to Gordon anyway. I was cast in the role of the little woman who just happened to be along. I did not realize then the importance of anonymity. There are times when you need to be as anonymous as the people who work in banks, and to play the game entirely by their rules. If they want loan applications to come in with shaven heads, you shave your head. And, sadly, you will never get a loan if you don’t have collateral. There is not a bank manager in the country prepared to take a chance on any venture no matter how brilliant the idea, without collateral. If we had not had the hotel to offer as collateral, The Body Shop would never have come into being. I often wonder how many fantastic ideas never came to fruition because of the lack of imagination of those people who sit behind desks all over the country and who are too frightened to take a gamble. There are only two ways of raising money: the hard way and the very hard way! «Making It Up»Once I had got the finance, I had to find out who could make up the products. I had been doing a lot of research on do-it-yourself cosmetics in Worthing public library and mixing ingredients in the kitchen, but I wasn’t getting on too well and every time Gordon went into the kitchen he slipped on the floor and nearly broke his neck. W were having a lot of trouble getting out mixture stable, although we had some good ingredients. Finally I thought, This is ridiculous, I’m not a cosmetic chemist or a pharmacist, so I approached a couple of the big cosmetics manufacturers, including Boots, to ask if they would make products for me. First, they were not the slightest bit interested in manufacturing the small quantities I needed, and second, they thought the ingredients I wanted to use were ridiculous. They had never heard of Rhassoul mud, they thought cocoa butter was something to do with chocolate, and they were indifferent to aloe vera. I think they thought I was completely mad. In the end I went through the Yellow Pages and found, under ‘Herbalists’, a small manufacturing chemist’s not far from Littlehampton who said they might be able to help me. I got in my little green van, drove straight over there and met this young man who had just taken over running the company. He was very nervous but very nice; I told him what I wanted, and we drew of a list of twenty-five possible products using those natural ingredients that were readily available – things like cocoa butter, jojoba oil, almond oil and aloe vera. I only wanted small quantities of each product and he wanted his money in advance – £700. That was the entire sum I had budgeted for product development. I had done a budget, of sorts. I’d allowed a certain amount for the overheads of the shop; some for rent and rates; some for ‘shop fitting’ – some basic pine furniture; and some for products. All this time I had been looking for a suitable site. I did not think Littlehampton was ready for the kind of shop I envisaged, and decided that the most sensible place to open would probably be Brighton, which was only twenty miles from Littlehampton and had a strong student culture supporting a number of thriving ‘alternative’ businesses. With its elegant Regency terraces Brighton was everything that Littlehampton was not – fashionable, up-market and expensive, yet popular with hippies, artists and the liberal intelligentsia. After traipsing the streets for what seemed like an eternity I finally found a small, scruffy, empty shop in a pedestrian precinct called Kensington Gardens, close to the center of the town. I did not pay too much attention to its conditions because I knew it was in a good position, so I happily paid six months’ rent in advance. Throughout this period Gordon was making preparations for his expedition. I was staggered at how little he was planning to take with him – he was relying on virtually nothing but an Ordnance Survey map to find his way across some of the most remote parts of South America. When he wasn’t poring over maps at the Royal Geographical society he helped me with the setting up of the shop. One evening we sat down and went through all the figures. Gordon worked out that I would need to make £300 a week to survive. ‘What happens id I don’t?’ I asked. ‘Give it six months,’ he replied breezily, ‘then pack it in and meet me with the kids in Peru.’ The shop was in a truly terrible state when I took it over – it had water running down the walls. I painted the whole place dark green, not because I wanted to make any environmental statement but because it was the only colour that would cover up all the damp patches. Then I hung larchlap garden fencing on the walls to hide the dripping water. «Necessity Is the Mother»This is how the famous Body Shop style developed – out of a Second World War mentality (shortages, utility goods, rationing) imposed by sheer necessity and the simple fact that I had no money. But I had a very clear image in my mind of the kind of style I wanted to create: I wanted it to look a bit like a country store in a Spaghetti Western. It is curious, looking back on it, how necessity accorded with philosophy. Even if I had unlimited funds, for example, I would never have wasted money on expensive packaging – the garbage of conventional cosmetics. And although I had set out to sell my products in a range of different sizes, I also needed to do so aesthetically, in order to make it appear as if the shelves were filled. With only twenty-five products on offer, the shop would have looked pathetic if there was just a single size of each, but with five sizes I could at least make sure that I filled a wall the bottles. The cheapest containers I could find were the plastic bottles used by hospitals to collect urine samples, but I could not afford to buy enough. I though I would get round the problem by offering to refill empty containers or to fill customers’ own bottles. In this way we started recycling and reusing materials long before it became necessity rather than a concern for the environment. Everything was done on a shoestring. I hired a designer to come up with the shop’s logo for £25, and I got friends round to help with filling the bottles and hand-writing all the labels. I certainly couldn’t afford to have the labels printed, and anyway I thought they looked nicer hand-written. We did all the filling in the kitchen of the St Winifred’s Hotel, decanting the stuff into jugs and then pouring it into bottles. Some of the products were pretty bizarre at the time, so I wrote postcards explaining exactly what was in each bottle, where the ingredients came from and they would do. Offering customers honest information would later become a cornerstone of out trading philosophy. A week before the shop was due to open I had the fright of my life when I got a letter from a solicitor threatening to sue unless I changed the name of the shop. It was incredible. There were apparently two funeral parlours in Kensington Gardens who claimed their business would be affected, that the bereaved would not want to hire a funeral director whose premises were close to a ‘Body Shop’. (There was alone a betting shop nearby which was taking bets on how long we would be able to stay in business).

All my life I have been intimidated by headmasters and solicitors, and it first I simply did not know what to do. But then it occurred to me I might be able to get some free publicity out of it. I made an anonymous telephone call to the local newspaper, the Brighton Evening Argus, and poured out a colourful story to a reporter about a ‘mafia’ of undertakers ganging up some poor defenseless woman who was only trying to open her own business while her husband was planning to go off and ride a horse across South America. I never heard any more from the solicitors and what I learned then was that there was no need, ever, to pay for advertising.

At nine o’clock on Saturday, 27 March 1976, the first Body Shop opened its doors for business at 22 Kensington Gardens, Brighton. By lunchtime I was so busy that I had to telephone Gordon to ask home to come and help. At six o’clock we closed the doors, sat down and counted the takings I had stuffed into the front pocket of my dungarees. I was thrilled: we had taken exactly £130.

There was a wonderful sunset as we drove home that night in our little green van. I was not just happy – I was euphoric.

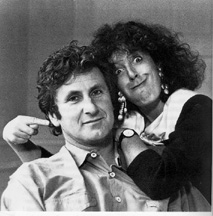

Many people perceive The Body Shop as a one-woman business. That’s so far from the truth! It didn’t even start that way – Gordon has always been involved from the beginning. We wouldn’t have got the initial funding from the bank if he hadn’t come up with the simple but effective strategy of playing by their rules. Gordon and I operate on the partnership principle – he does his bit, and I do mine, but we do it together, with a common purpose….

|